Using Scaffold 22 as a lightweight example, I’d like to examine how such a world and narrative is built, and how plot options and player agency are created.

Let’s assume a few basics: the world and setting are known and established, at least in theory. The basic narrative has been written. This was the state of Scaffold 22 after it’s first alpha release. There was a single-threaded plot. The game was linear. This is how we think about stories: as linear experiences – even if it’s a dynamic structure, we treat ‘our’ experience as a linear one. We don’t jump between options. We imagine a book, a movie, a memory. There’s a single progression of events that holds everything together. This is very much a manageable experience, both as a writer and a designer. You write in one direction, edit in one direction; everything lines up in the final version. That version can then be submitted to a publisher or editor, and they’ll be able to offer suggestions based on how they perceived the narrative.

A tree… thing with branches!

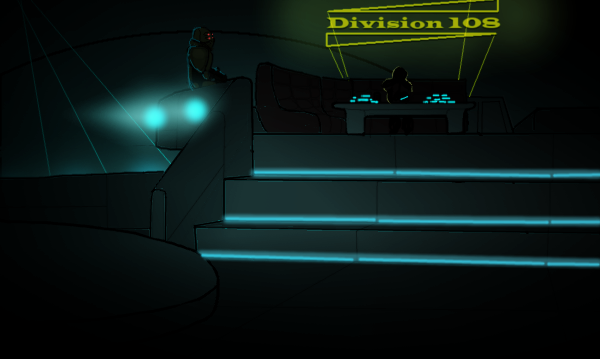

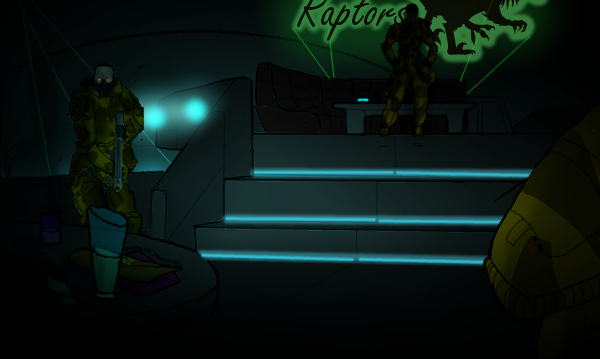

Technically, the issue is simple to examine. By introducing a branch, all those narrative elements we so painstakingly laid out in a linear fashion can (potentially) be invalidated by a player choosing to go an alternate route. In Scaffold 22, you’re presented with such a notable choice roughly 1/3 of the way into the game. Upon returning to or otherwise visiting the Riptide, a major club and party venue, you’re asked to choose between two factions:

A street gang turned mercenary outfit the player character used to run; this is a known quantity the player will most likely familiar with unless they opted for extremely quirky early-game progression.

A xenophobic mercenary group staffed by former members of the player character’s gang; this is a previously unexplored element in the narrative and represents a (presumably) unknown quantity.

In Scaffold 22, the Raptor / Division 108 branch has a major effect on the world. Not only does the plot change by locking out or allowing different missions, but the characters you meet and enemies you might potentially face are altered. Different gear options are unlocked. Player progression and perception of the narrative is altered for the remainder of that play-through.

To achieve this sense of divergence, there are hundreds of dialog segments which have two versions: one for Raptors and one for Division 108. Numerous missions have two progressions: one for Raptors and one for Division 108. Narrative options and gameplay elements are made available or locked out. Simply put, the volume of total content in Scaffold 22 is, as a direct result of this choice, doubled.

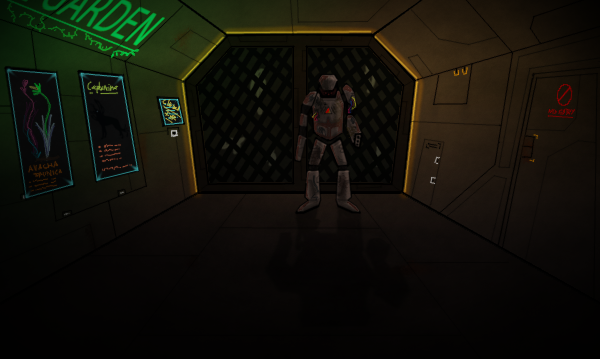

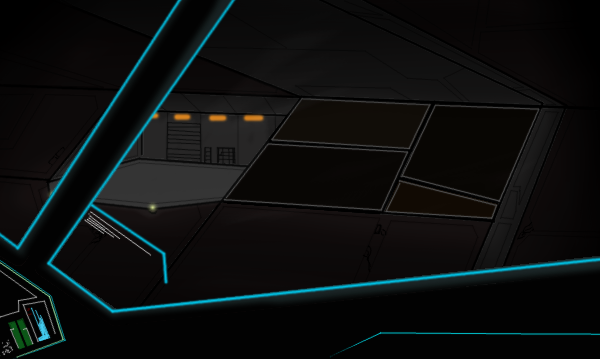

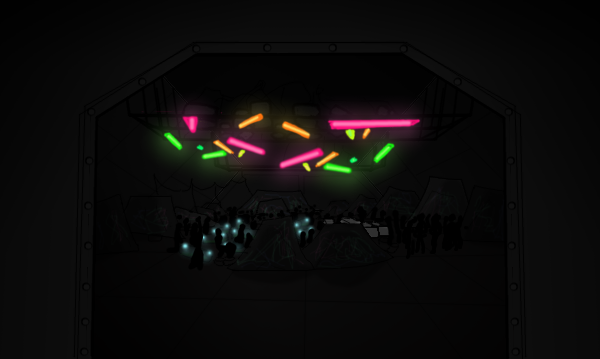

Basic Content (Riptide VIP Area)

Altered Content (Riptide VIP under Division 108 Control)

Transition Scene (Division 108 attacks the Riptide)

As the name implies, a branch point is the point in time (and code) where a narrative branches between two or more options. Imagine a tree. Each branch leads to more sub-branches and so on. Pretty basic stuff so far.

In practice however, that tree is simply impossible to manage. There would be too much specific content resulting from each branch – a workload even the biggest development team couldn’t handle. We have to encourage the perception of such such a structure instead, and this is where branch points come into play. Any given branch point may or may not actually alter significant portions of the story – oftentimes, content is written entirely independent of the branch. But, in order to make the branch seem significant, it has to be presented well. A branch has to feel natural and not suspend disbelief. And the branch has to hide just how simplistic the narrative really is behind the scenes.

The most noticeable branch point in Scaffold 22 is the aforementioned Raptors / Division 108 split; it’s an overt change of the game’s entire tone. The game asks: do you want to maintain the more liberal status quo but accept criminality and corruption, or enforce a totalitarian, xenophobic rule that stamps out criminals and corruption by brute force? It also asks a few other questions and punishes some options but the point stands; this is a major shift in narrative tone, and a significant moment of character development.

Illustration prior to the aforementioned branch point

What about those other faction branches? Well, they’re a bit more subtle. Three of those are criminal subfactions who prefer to stay out of the limelight. As a result, their branch points are hidden in the narrative. And the fourth faction is your original employer – there isn’t even a noticeable branch there; simply following the main plot line without doing anything to change the status quo will ‘branch’ at the appropriate point, without the player ever noticing.

See how location of branch points are significant to the tone of the narrative? Status quo means nothing is changed. Criminal factions in the shadows are hidden and hard to find. Overt actors are presented as such to the player directly. By placing these branches at the right places, the player is building their perception of the game as a series of diverging choices that result in a tree-like structure.

In actuality, they’re narrowing down their narrative to a specific tone by choosing a specific path (imagine: chopping branches off the tree). If done well, and the narrative flows properly, they’ll never realize they’re actually doing this – or that the tree is simply a (well placed) sequence of choices that may or may not actually relate to one another. We’ll get to all that in more detail later. First, we have to take a moment to examine how these branches are presented to the player…

Obviously, branching willy-nilly and at arbitrary points in time doesn’t work. The player will be confused and not care about the choices. So the narrative has to lead up to every potential branch – or at least try. You can never quite guarantee a player will care about a branch, or even realize what’s going on.

The aforementioned Raptor / Division 108 split? Well, depending on progression that can fly right past the player. They’ll be surprised by the event. That’s actually intentional, as the narrative builds up the choice as a surprise raid by Division 108, timed so that it (hopefully) occurs at a point where the player is used to the status quo. It’s shock and awe factor is supposed to jar the player out of their complacency and force them to consider the wider implications of their choices on the world. This is in fact a trick: there aren’t more than a dozen. But, by presenting it as such, we can lead the player to believe their future choices will be SIGNIFICANT! They’re really significant in lower-case letters and with a whispered consequence, but don’t tell anyone.

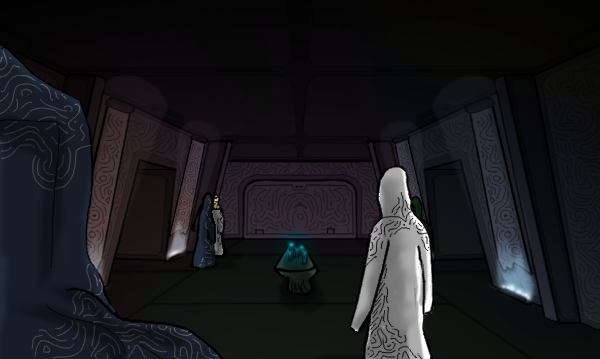

A subtler lead-up to the Cybercult branch

But there’s another issue: every major branch risks locking out content. In the above example, let’s assume we chose Wilkin’s Raptors. Suddenly, all Division 108 related content is unavailable. One third of the way into the game, 50% of the content has been locked out by a single decision! The game’s narrative couldn’t care less, of course – the player made their choice and is now dealing with the consequence. From a gameplay and development perspective however, that’s bad. Not only do we have to write more content, but we have to carry double the load for every choice. Multiplied by dozens of other choices and it’s impossible to handle. Time for another trick.

In order to avoid locking out too much content, we present the character with branches – and an option to opt out or into the consequences. Even the MAJOR! branch in Scaffold 22 isn’t quite definitive. You can slaughter Division 108 and still meet their employer. Or you can wipe out the Raptors and still pursue the main plot line without their meddlesome influence. There are side quests and modifiers to the main quest line designed to handle both cases (actually, a variation on the same mission that is re-used in several other places) and only one definitive point per branch where the player has to decide if they do or don’t want to go that route.

Gameplay and narrative wise, this is achieved by separating the branch point from the point of absolutely no return; that moment when the player decides to make a change to their personal narrative from which they cannot recover and cannot back out of. Every faction has one of these, and every major decision can be opted out of (or into) at various points. Opt out of every option consequently and the narrative defaults back to its ‘normal’, linear progression as originally written and eventually ‘locks in’ to that storyline.

Default (Church of Eden) plot locks in

Of course this is still all a trick. They’ve already opted in or out of major choices. But, by giving the player a little leeway, we’re allowing them to breathe, to decide, consider, re-think, and ultimately settle for a given progression, not when the game forces them to but when they want to.

We’ve talked a lot about the basics in abstract terms, and how they cause expoential workload for both the writer and developer, but let’s look at some specific techniques and tricks which can be used to lessen the workload without harming the experience.

Somewhere in the depths of Scaffold 22 is a character named Commisaria Varai. She appears in several events related to criminal behavior, a single side mission, and the lead-up to the ‘default’ ending. She can be killed. She can come to tolerate you. Or she can become a tertiary antagonist (seriously, she’s an annoying character).

Given the number of potential outcomes of interacting with her, we want to avoid tying her into the main story line too often. Why? Because, if she’s dead, that means someone else has to take her place. If she tolerates you, that requires unique dialog, and if she hates you, another set of lines for that eventuality. Multiply those cases over the total number of times Commisaria Varai appears in the narrative, and consider there are several other characters with similar reactions, and one quickly realizes why her narrative must be isolated to prevent content bloat.

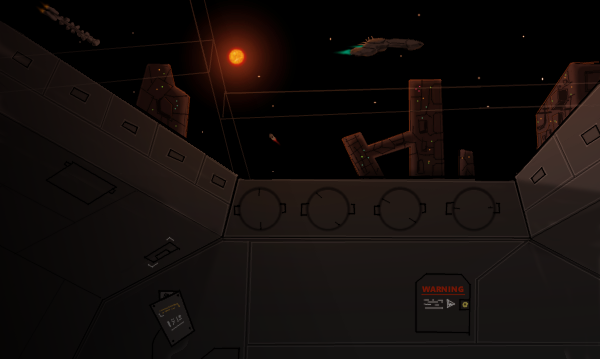

If all those stars out there had a backstory, that would be bloat (note: one does)

I use this technique a lot in Scaffold 22 to avoid choices spilling over into impossibly convoluted situations, where hundreds of conditions need to be checked to build a simple scene. Sub-plots are most often isolated entirely from the main story, barring occasional reference. This significantly reduces the workload and keeps the narrative manageable.

I hinted at this earlier, but virtually every choice in Scaffold 22 is binary opt-in or opt-out. This sounds simplistic, but bear with me. By making sure the vast majority of outcomes have only two states, I reduce the number of eventualities I have to cover as a writer and designer.

To hide this simplistic structure, numerous binary choices are layered on top of one another. Let’s return to the old Raptor / Division 108 example for a moment. A player who chooses the Raptors and then chooses to speak to Division 108’s employer will have a vastly different experience from someone who chooses Division 108 and kills their employer.

Division 108’s Employer (spoiler?)

Playing Scaffold 22, you’ll rarely notice this is happening. Pick the code apart and you’ll quickly realize that you aren’t really being given as much freedom as you’re led to believe. This is what I meant earlier with restricting options; narrowing down the narrative while leading the player to believe they have more options than they do. That’s a core element of writing interactive stories and branching narratives. The player’s experience has to be narrowed down so that we (as humans) can perceive a single plot thread – our experience. The trick is doing this without telegraphing the reality of the situation to the player and making them feel like the experience is hollow or forced.

Another useful trick related to exclusion is inconsistent plot lines. In Scaffold 22, if you go with Division 108 and pursue their plot, you immediately invalidate any and all content which relates to the player pursuing the default (Church of Eden) narrative. And vice versa. Viewed in a void, these two narratives are wildly inconsistent: pursuing the Church ending, you’re liked by character X. Go another route and X will despise you. Objectively these stories cannot coexist. The events don’t add up and, if you were to change a few variables at runtime, the narrative would fall apart.

Since that doesn’t happen in practice however, we can simply treat those two plots as entirely different progressions of the underlying narrative. By being mutually inconsistent, and by ensuring those two plots don’t have to coexist, we can reduce the number of contextualized content that needs to be created.

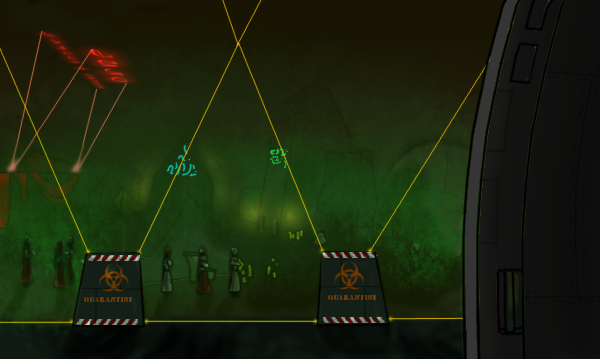

Contextual: this place usually isn’t poisoned

Provided there are enough other progressions to hold the player’s interest, this shortcut won’t become apparent, as the player is still facing the cumulative consequences of all their actions. That character X happens to be ignored entirely up until the point they become relevant again… well, the player’s imagination will fill the gap.

I have a general rule about encounters: there should be at least three options available to the player at all times. Scaffold 22 goes out of its way (most of the time) to implement this. By offering more than a binary choice (even if the result is binary, see above) the player is forced to think a little more about how they want to act.

Even a simple yes/no choice can be enhanced with a third option: tell me more. The player will still be forced to decide eventually, but the third option allows a little more freedom. They can opt to decide immediately or learn a bit more before committing. These sort of options (even if they are bogus) are essential to maintaining the illusion of agency – and contextualizing choices, especially when there really isn’t anything to choose between.

Unless a specific event has to be explicitly mentioned, don’t mention it. This avoids having to (re)write countless scenes for every possible eventuality. Any given character or event that is not the focal point of a discussion can be referred to vaguely as ‘that guy’ or ‘that thing’, allowing the player to infer significance based on their personal experience. This cuts down on workload again, while maintaining narrative consistency.

Vague artwork reduces workload too

This is also used with discussions of backstory. A player who hasn’t read Scaffold 22’s extensive Codex entries will be able to infer what might have happened, while one who has will immediately associate mentioned events with what they read. In the case of backstory and fluff, this technique is in fact a necessity – I can’t guarantee the player picked up on the significance of any given fluff article even if they read the Codex entry (which I can’t reliably determine anyways), so let’s just be vague about it and hope for the best.

Another way to avoid overloading the story with intersecting branches is offer content that is of purely mechanical value, but has little to no narrative significance. A good example of this in Scaffold 22 is the ‘Highborn Palace’, a slaver den that the player can rule over or exterminate – or simply leave alone. There is only one plot-relevant narrative branch that occurs here, and one tangentially important quest option. Beyond that, this entire location is divorced from the main narrative, and exists within its own little microcosm that’s occasionally affected by external events but never in a significant way.

Gameplay wise however, Highborn Palace offers access to a new player class, new gear, and an alternate source of income (and a boss fight to test one’s gear and skills). By divorcing this location entirely from the rest of the story, we don’t have to ever include it, and never have to check how the player handled discovering the location (if they even did). There are two other locations in the game that follow this pattern, and numerous ‘flavor’ encounters that do the same.

The aforementioned ‘High Palace’

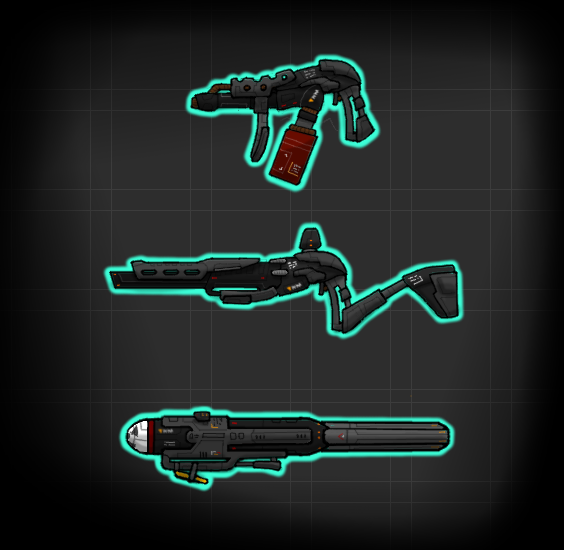

Numerous options presented to the player – options that are significant to the player’s perceived experience – are purely mechanical. The weapons they carry. The outfit they chose. The augments they installed. None of these are checked by the game’s narrative except in very specific and highly situational circumstances. By offering these customization options to the player however, the player can define who they are as a character without affecting the narrative – or the narrative affecting them.

Mechanical Options: A selection of potential Weaponry

Creating a branching narrative and integrating it into satisfying gameplay is a challenge for any developer to say the least. It requires a lot of patience, experimentation, shortcuts, tricks, and a good sense of how complex systems interact – not just on a technical level. Branching narrative is as much about emotion and player experience as it is flags set in code.

In-game events have to be rich, varied, unique. Gameplay has to be consistent. Narrative has to be narrowed down to a single, coherent plot. Everything seems to be pulling in different directions and yet the gameplay experience as seen by the player has to be consistent. Viewed from a distance, all this may seem insurmountable and impossible to handle. Broken down, with a few dirty tricks to help along the way, it’s entirely doable even by a small team.

Scaffold 22 isn’t the odd one out. It’s the result of one developer who wanted to figure out how to write a branching, narrative-focused role playing game. Sure, it may have taken a little longer than some games, and may not be the most technically impressive product, but I consider a two-year development cycle to be reasonable for the product it produced. I had to learn a lot along the way though, iterate over content many times, until I found a system that worked.

I hope that this article will shed a little light on the mystery of branching narratives, and help fellow developers create similarly complex works (be they text-based such as my game or fully interactive, 3d worlds).